Governor Signs Controversial Legislation Providing New Rules for Builder’s Remedy Projects

On September 19, 2024, the Governor signed a suite of housing bills, including two important bills revamping the much-publicized “Builder’s Remedy” provisions of the Housing Accountability Act (“HAA”). Assembly Bill (“AB”) 1886, authored by Assemblymember Alvarez, confirms existing requirements for a local government’s housing element to be in “substantial compliance” with the State Housing Element Law, confirming technical assistance from the California Department of Housing and Community Development (“HCD”) and recent trial court decisions. AB 1893, authored by Assemblymember Wicks, overhauls the Builder’s Remedy provisions of the HAA for the first time since their enactment over 30 years ago. This update outlines the major changes to Builder’s Remedy enacted through AB 1886 and AB 1893.

Builder’s Remedy Background

The portion of the HAA referred to as “Builder’s Remedy” applies when a local agency has not adopted a housing element that substantially complies with State Housing Element Law, and it precludes such agencies from denying a housing development project on the basis that the project is inconsistent with the agency’s zoning ordinance and general plan land use designation. Builder’s Remedy incentivizes local jurisdictions to timely adopt compliant housing elements and to rezone property identified in their housing sites inventories to allow for housing development.

Although Builder’s Remedy has been included in the HAA for decades, it gained prominence in 2021-22, during the 6th Housing Element Cycle (the most recent state cycle of reviewing and requiring updates to all local general plan housing elements). In the 6th Cycle, the state dramatically increased Regional Housing Needs Allocations (“RHNA”) and HCD heightened its scrutiny of housing elements, in response to California’s worsening housing crisis. Many jurisdictions failed to adopt or obtain HCD certification of their 6th Cycle housing elements prior to the statutory deadline.

As developers and local agencies began to grapple with implementation of Builder’s Remedy, it became evident that the HAA provides little guidance about how to submit or process Builder’s Remedy applications. Although HCD stepped in to provide technical assistance, local agencies have not uniformly followed HCD’s guidance. AB 1886 and AB 1893 clarify many ambiguities and fill many interpretative gaps in Builder’s Remedy law, making it easier for qualifying projects to use this important housing entitlement tool.

New Definition of “Builder’s Remedy Project”

AB 1893 enacts a new statutory definition of a “Builder’s Remedy Project.” Effective January 1, 2025, new projects will be eligible to use Builder’s Remedy only if the four elements of this new definition, described below, are satisfied. (As used in this alert, “Builder’s Remedy Projects” refers to projects that meet the AB 1893 definition.)

1. No Substantially Compliant Housing Element

Under both existing law and AB 1893, Builder’s Remedy is available only if the local agency did not have a substantially compliant housing element on the date the housing development project was deemed complete, typically meaning the date a complete SB 330 preliminary application was submitted. For applications deemed complete after January 1, 2025, however, AB 1893 limits the availability of Builder’s Remedy in such jurisdictions to housing development projects that meet the new definition of a Builder’s Remedy Project. AB 1893 further provides that the local agency has the burden of proof to establish that the application is not complete.

In response to arguments from local agencies that they could “self-certify” their housing elements, AB 1886 affirms that a housing element is not “substantially compliant” until determined so by HCD or a court. AB 1886 also confirms that, for purposes of processing Builder’s Remedy applications, a housing element is not considered in substantial compliance unless it was in substantial compliance when an SB 330 preliminary application was submitted (or when a complete formal application was submitted if no preliminary application was submitted). In other words, housing element noncompliance is “vested” at the time of a preliminary application or, if none, a complete formal application. These provisions are consistent with technical assistance previously rendered by HCD and trial court decisions interpreting Builder’s Remedy, and AB 1886 confirms that they are declarative of existing law.

2. Housing Affordability

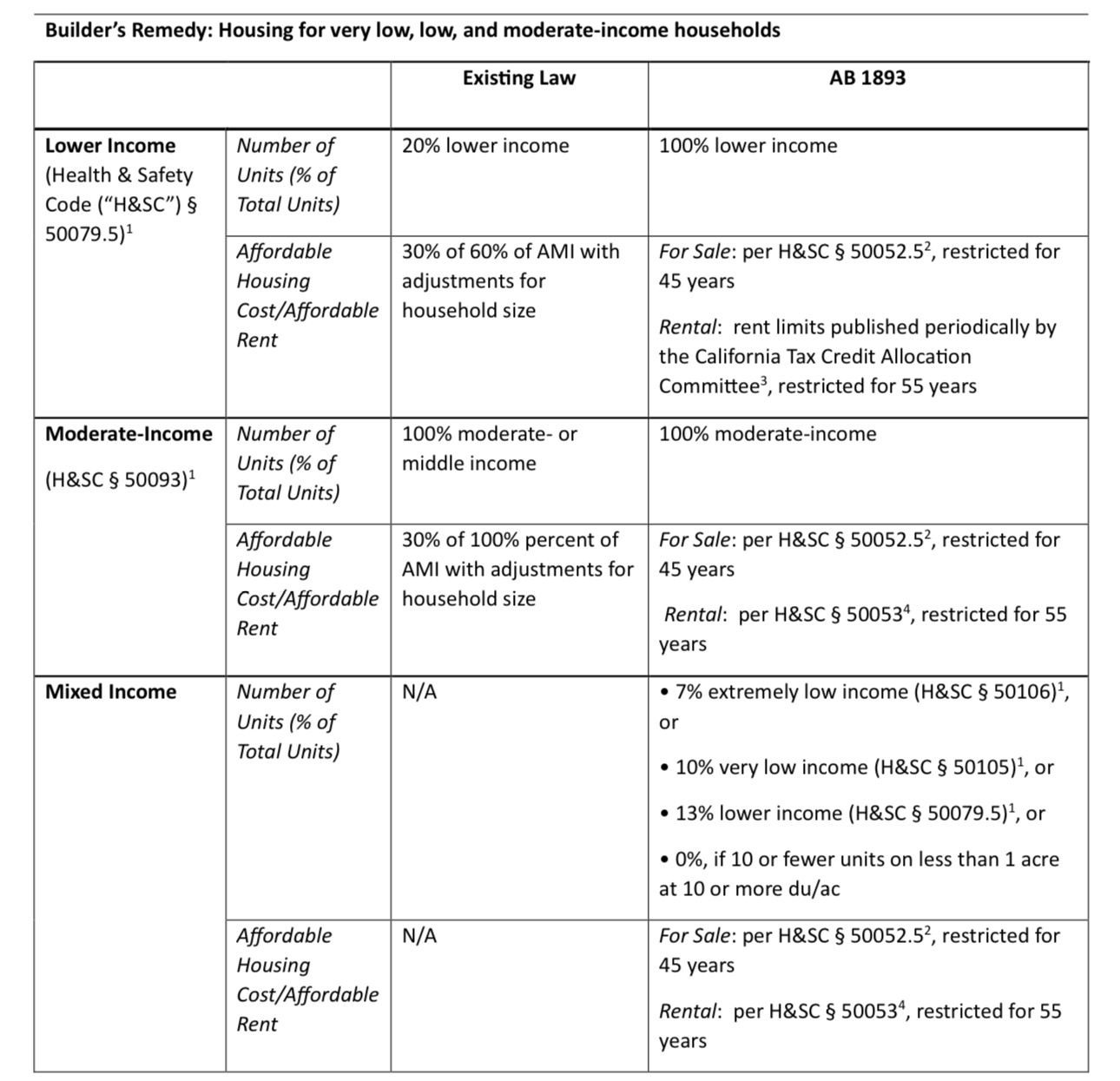

Both existing law and AB 1893 require a housing development project using Builder’s Remedy to provide “housing for very low, low-, or moderate-income households.” Under current law, this requirement means either (i) at least 20 percent of the total units must be sold or rented to lower-income households and made available at a housing cost that does not exceed 30 percent of 60 percent of area median income (“AMI”), or (ii) 100 percent of the units must be sold or rented to moderate income households and made available at a housing cost that does not exceed 30 percent of 100 percent of AMI. The current HAA does not define “total units.”

AB 1893 expands the options for meeting the income and housing cost requirements to use Builder’s Remedy. Effective January 1, 2025, “housing for very low, low-, or moderate-income households” for purposes of qualifying as a Builder’s Remedy Project means housing for lower, moderate-, or mixed income households as set forth in the table below. (A stand-alone version of this table is available here for ease of reference.) AB 1893 also incorporates the definition of “total units” from the Density Bonus Law (“DBL”), which excludes units added by a density bonus awarded under the DBL or any local law and includes units designated to satisfy local inclusionary zoning requirements.

1 Income Definitions

“Extremely low-income households” means persons and families whose incomes do not exceed 30 percent of AMI, adjusted for family size.

“Very low income households” means persons and families whose incomes do not exceed 50 percent of AMI, adjusted for family size.

“Lower income households” means persons and families whose incomes do not exceed 80 percent of AMI, adjusted for family size.

“Moderate-income households” means persons and families whose incomes exceed the income limit for lower income households but do not exceed 120 percent of AMI, adjusted for family size.

2 Affordable Housing Cost Definitions

For extremely low income households, 30% of 30% of AMI, adjusted for family size.

For very low income households, 30% of 50% of AMI, adjusted for family size.

For lower income households whose gross incomes exceed the maximum income for very low income households, 30% of 70% of AMI, adjusted for household size, with the ability for the jurisdiction to increase to 30% of gross income if gross income exceeds 70% of AMI.

For moderate income households, 35% of 110% of AMI, adjusted for household size, with the ability for the jurisdiction to increase to 35% of gross income if gross income exceeds 110% of AMI.

3 California Tax Credit Allocation Committee Rent Definitions

See California Tax Credit Allocation Committee website. The 2024 income and rent limits are available here.

4 Affordable Rent Definitions:

For extremely low-income households, 30% of 30% of AMI, adjusted for family size.

For very low income households, 30% of 50% of AMI, adjusted for family size.

For lower income households whose gross incomes exceed the maximum income for very low income households, 30% of 60% of AMI, adjusted for family size, with the ability for the jurisdiction to increase to 30% of gross income if gross income exceeds 60% of AMI.

For moderate income households, 30% of 110% of AMI, adjusted for household size, with the ability for the jurisdiction to increase to 30% of gross income if gross income exceeds 110% of AMI.

3. Maximum and Minimum Density

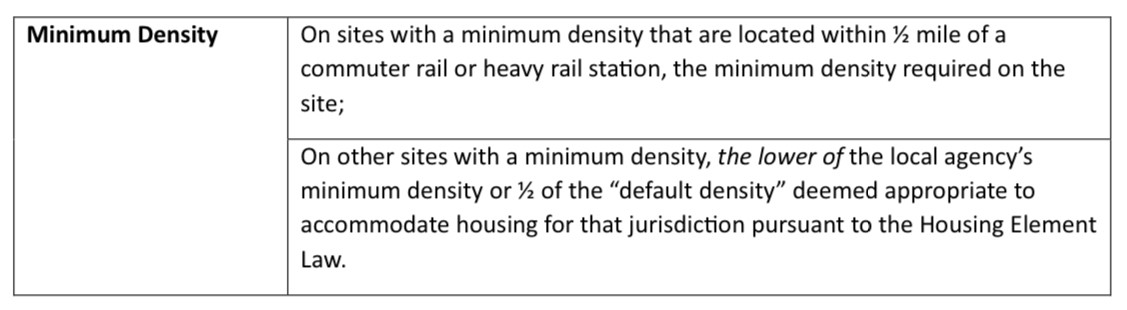

AB 1893 adds new maximum and minimum density limitations for Builder’s Remedy Projects. These requirements stem from political reactions to particular projects, including a San Francisco project near Ocean Beach that proposed to use the Density Bonus Law to construct a high-rise in an otherwise low-density neighborhood and several San Jose projects that proposed to use Builder’s Remedy to decrease minimum density on transit-proximate sites.

To qualify as a Builder’s Remedy Project under AB 1893, the maximum density of a housing development project (before application of any density bonus) cannot exceed the greatest of:

To qualify as a Builder’s Remedy Project under AB 1893, the minimum density of a housing development project on a site that has a minimum density under local agency rules cannot be less than:

4. Proximity to Industrial Uses

AB 1893 adds new restrictions on the use of the Builder’s Remedy in industrial areas. These restrictions represent a political response to fiscal arguments by local agencies seeking to prevent conversion of their job-producing lands to residential uses. Specifically, AB 1893 provides that a Builder’s Remedy Project cannot abut a site where more than one-third of the square footage on the site has been used within the past three years by a heavy industrial use or a Title V industrial use, as those terms are defined in Government Code section 65913.16.

New Rules for Implementation of Builder’s Remedy

1. Builder’s Remedy and Local Affordable Housing Requirements

AB 1893 provides new guidance regarding the interplay between Builder’s Remedy and local affordable housing requirements, eliminating much of the uncertainty that HCD has struggled to reconcile under existing law. AB 1893 provides that, if a local agency had local affordable housing requirements on January 1, 2024, that required a greater percentage of affordable units or a deeper level of affordability than required for a Builder’s Remedy Project, the local agency generally can require a housing development for mixed-income households to comply with its requirements, provided that it finds that the requirements would not render the housing development project infeasible.

Nonetheless, the local agency cannot apply its local affordable housing requirements to require a Builder’s Remedy Project for mixed-income households to provide more than 20 percent affordable units, and if 20 percent affordable units are required, the required affordability level cannot be deeper than lower income. Effectively, this provision maintains the status quo of existing Builder’s Remedy law as a ceiling on affordability requirements.

Critically, the local agency cannot require a Builder’s Remedy project for mixed-income households to comply with any other aspect of a local affordable housing requirement. AB 1893, however, adds a requirement that the affordable units in a mixed-income Builder’s Remedy Project have a comparable bedroom and bathroom count as the market rate units.

AB 1893 also confirms existing law establishing that affordable units in a mixed-income Builder’s Remedy Project count toward satisfying local affordable housing requirements and vice versa.

2. Builder’s Remedy and Density Bonus Law

AB 1893 provides clarification and new benefits for Builder’s Remedy Projects using the DBL. Specifically:

- Builder’s Remedy Projects are entitled to two incentives or concessions in addition to those granted under the DBL.

- The base density under the DBL for a Builder’s Remedy Project is the maximum density allowed for a Builder’s Remedy Project. A local agency must grant a density bonus based on the number of units proposed and allowable for a Builder’s Remedy Project.

- A Builder’s Remedy Project that provides extremely low-income units is entitled to the same density bonus, incentives or concessions, and waivers as a project that dedicates three percent more units to very low income households pursuant to the DBL.

AB 1893 also confirms existing law establishing that affordable units in a Builder’s Remedy Project count toward satisfying the DBL requirement.

Compliance with Objective Standards

AB 1893 clarifies several important points regarding the applicability of a local agency’s “objective standards” to Builder’s Remedy Projects. Specifically:

- A local agency can require a Builder’s Remedy Project to comply with objective standards that would have applied to the project if the general plan designation and zoning classification permitted the density and unit type proposed. If the local agency has no such designation and classification, the applicant may identify objective standards in a different designation and classification that facilitates the density type and unit type proposed.

- The requirement for compliance with objective standards does not limit a Builder’s Remedy Project from using the DBL.

- A local agency generally cannot apply objective standards that render the project infeasible or preclude a project that meets applicable objective standards, as modified though use of the DBL, from being constructed as proposed.

4. Compliance with Other Requirements

AB 1893 responds to a variety of arguments made by local governments to obstruct use of Builder’s Remedy by clarifying what local agencies cannot require. Specifically, Builder’s Remedy Projects are deemed in compliance with residential density standards for purposes of the Affordable Housing and High Road Jobs Act of 2022 (AB 2011/AB 2243) and with objective standards for purposes of the streamlined approval process available under Government Code section 65913.4 (SB 35/SB 423).

Builder’s Remedy Projects also are deemed consistent, compliant, and in conformity with an applicable plan, program, policy, ordinance, standard, requirement, redevelopment plan and implementing instruments, or other similar provision for all purposes, a response to the practice of some local agencies to require Builder’s Remedy applications to include general plan and zoning amendment applications.

Pipeline Provisions

AB 1893 establishes “pipeline” protections for housing development projects that had a deemed complete application before January 1, 2025. Specifically, an applicant for such a project may choose to be subject to the Builder’s Remedy provisions that were in effect when the preliminary application was submitted or, if the project meets the new definition of a Builder’s Remedy Project, may choose to be subject to any or all of the Builder’s Remedy provisions in effect as of January 1, 2025. AB 1893 does not restrict the timing of the applicant’s election. Further, for Builder’s Remedy applications deemed complete before January 1, 2025, the applicant may revise its project to meet the new definition of a Builder’s Remedy Project without losing its SB 330 vesting status, even if the revision results in a 20 percent or greater change in project square footage or number of units.

Notably, the legislative findings in support of AB 1893 note that the Builder’s Remedy amendments are intended to clarify existing law and should not be interpreted as constraints or impediments to processing current Builder’s Remedy projects that are deemed complete.

Conclusion

The impetus for the overhaul of Builder’s Remedy came from local jurisdictions and residents fearful of the loss of local land use control, as well as developers frustrated by the obstacles local agencies were able to impose given the lack of clear implementation guidance in the existing statute. The bill was heavily negotiated throughout the session. Thanks to the leadership of Assemblymember Wicks and pro-housing advocates, the negotiations remained framed by a reminder that Builder’s Remedy applies only to jurisdictions that have failed to meet their state-mandated housing obligations. On balance, the final legislation largely benefits housing development by injecting greater clarity and certainty into the processing of Builder’s Remedy applications.

Please contact an author of this alert or any member of our Land Use & Natural Resources Team should you have questions about Builder’s Remedy.